Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus)

Painting by Missy Dunaway. Created with acrylic ink on paper. 30x22 inches (76x56 cm)

Painting Key

Fauna: 2 Peregrine falcons

Objects: An assemblage of falconry gear (6 bells, 3 hoods of early 17th-century English designs, 1 harness with leash, 2 hood maker's awls, 7 jesses), 4 peregrine falcon eggs, 15 peregrine falcon feathers, 1 imped (repaired) peregrine falcon feather

Shakespeare's Peregrine Falcon

Occurrences in text: 13 “falcon,” 1 “tassel-gentle,” 1 “tercel”

Plays: As You Like It, Henry VI Part II, Henry VI Part III, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, Richard II, Romeo and Juliet, Taming of the Shrew, Troilus and Cressida, The Winter’s Tale

Poems: “The Rape of Lucrece,” “Venus and Adonis”

We are meeting the peregrine falcon in November, the best month for falconry. Falconry is most popular in the fall because raptors have better visibility for hunting when the leaves are off the trees. Falconry plays a giant role in Shakespeare's world. I am one-third of the way through my Birds of Shakespeare project, so falconry-related summaries like this one will likely evolve as I learn more about the sport.

Shakespeare peppers falconry terminology throughout his dialogue, similar to how a baseball lover uses the phrases "home run," "out of the park," and "swing for the fences" in everyday conversation. The references are difficult to catch because they effortlessly weave in and out of casual dialogue. Should every mention of a jess, hood, pitch, or mantling count as a reference to the falcon? I have decided to exclude these terms from the peregrine falcon’s count, since they could refer to other birds used in falconry, such as the goshawk, merlin, and kestrel.

In Shakespeare’s world, the general term of “falcon” only applies to a female peregrine falcon.[1] A male peregrine falcon is called a “tercel” or “tassel-gentle.” “Tassel” and "tercel” mean "a third," because the male is one-third the size of a female.[2]

In the balcony scene of Romeo and Juliet, Juliet appropriately describes Romeo as a male peregrine falcon when she calls him back to her window to continue their secret conference:

Romeo and Juliet (Act II, Scene 2, Line 169)

JULIET: Hist, Romeo, hist! O, for a falc'ner's voice

To lure this tassel-gentle back again!

Bondage is hoarse and may not speak aloud,

Else would I tear the cave where Echo lies

And make her airy tongue more hoarse than ⌜mine⌝

With repetition of "My Romeo!"ROMEO: It is my soul that calls upon my name.

How silver-sweet sound lovers’ tongues by night,

Like softest music to attending ears.

This is a flattering description of Romeo, as the peregrine falcon is a handsome bird crowned the world's fastest animal, reaching up to 200 miles per hour in a power dive, or "stoop." Peregrine falcons will fly to great heights and dive on other birds mid-air, knocking them unconscious or killing them on impact. They are athletic and lethal but also gentle (by raptor standards) and easily hand-tamed for falconry.

The word "gentle" describes the peregrine falcon’s demeanor, but it also refers to social status. Falconry was a noble vocation, but even within the sport, the peregrine falcon was a noble species. Every bird of prey was flown by a different social class: kings carried gyrfalcons, the nobility flew peregrine falcons, high-born ladies had merlins, the clergy used sparrowhawks, and commoners kept kestrels.[3] When Juliet calls Romeo a tassel-gentle, she not only depicts him as handsome and powerful, but she also suggests his gentile social status and nobility.

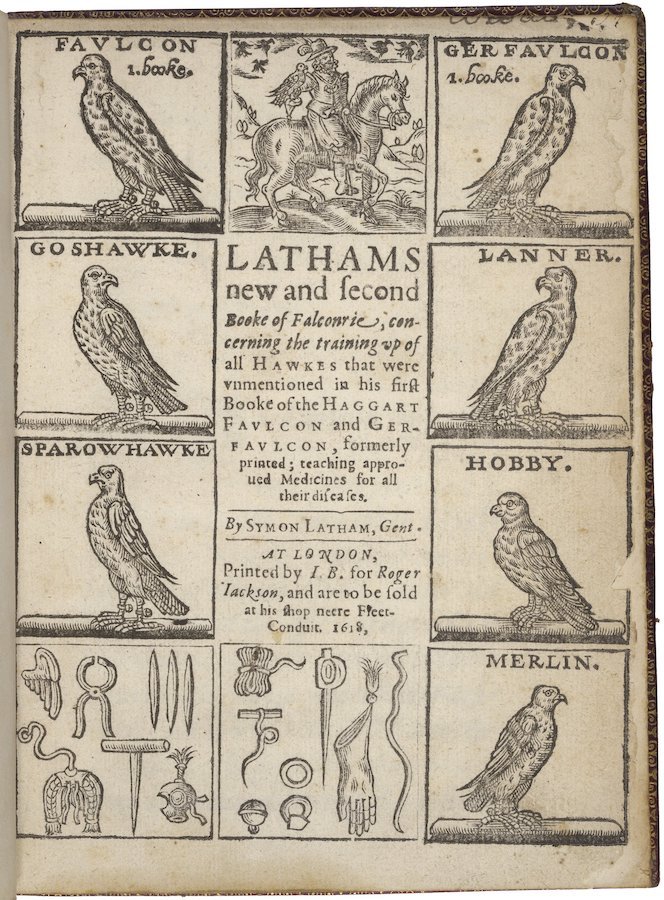

An illustration of raptors employed in falconry, including the female peregrine falcon, known simply as a “falcon,” from Lathams new and second booke of falconrie by Symon Latham (1618). Folger Shakespeare Library

The female peregrine falcon was considered the more powerful huntress that targeted large birds like herons and rooks.[4] In Macbeth, two noblemen recount seeing a mighty female peregrine falcon killed by a mousing owl—a strange sight, as small owls are usually prey to falcons. This power inversion foreshadows the murder of King Duncan at the hands of one of his subjects, Macbeth.

Macbeth (Act II, Scene 4, Line 13)

OLD MAN: ’Tis unnatural,

Even like the deed that’s done. On Tuesday last

A falcon, tow’ring in her pride of place,

Was by a mousing owl hawked at and killed.ROSS: And Duncan’s horses (a thing most strange and

certain),

Beauteous and swift, the minions of their race,

Turned wild in nature, broke their stalls, flung out,

Contending ’gainst obedience, as they would

Make war with mankind.OLD MAN: ’Tis said they eat each

other.ROSS: They did so, to th’ amazement of mine eyes

That looked upon ’t.

“Peregrine” means “wandering,” which alludes to the peregrine falcon’s wide territory and expansive global distribution. It is a common raptor that can be found on every continent. However, the global population took a major hit between 1940 – 1970 due to widespread use of organochlorine agricultural pesticides. The peregrine falcon teetered on the edge of extinction by preying on smaller birds that had ingested seeds treated with DDT and HEOD. Contamination resulted in thin eggshells that could not carry chicks to term.[5]

Due to a mixture of mercury, lead, organochlorine poisoning, habitat degradation, and collisions with cars and buildings, the peregrine falcon population fell to historic lows in 1963.[6] Thanks to the banning of organochlorine and conservation efforts, the species has made a stunning recovery and is currently considered "least concern."[7]

My peregrine falcon painting includes an assemblage of falconry gear, including two early 17th-century English falcon hoods sourced from the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Endnotes

[1] Phipson, Emma. Animal Lore of Shakespeare's Time. Glastonbury, The Lost Library, Kegan Paul, 1883. p. 247.

[2] Greenoak, F., All The Birds of the Air, 2nd ed, (Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd., 1981), 89.

[3] Harting, J., The Birds of Shakespeare, (London: John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row, 1871), 52-53.

[4] Phipson, Emma. Animal Lore of Shakespeare's Time. Glastonbury, The Lost Library, Kegan Paul, 1883. p. 247.

[5] White, C. M., Clum, N. J. Cade, T. J., and Hunt, W. G., "Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus)," Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, March 4, 2020.

[6] Greenoak, F., All The Birds of the Air, 2nd ed, (Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd., 1981), 89.

[7] White, C. M., Clum, N. J. Cade, T. J., and Hunt, W. G., "Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus)," Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, March 4, 2020.