Eurasian Blackbird (Turdus merula)

Painting by Missy Dunaway. Created with acrylic ink on paper. 30x22 inches (76x56 cm)

Painting Key

Fauna: 4 Blackbirds (Turdus merula), prey: butterflies (1 chequered skipper, 1 grizzled skipper, 1 holly blue, 3 swallowtails) and caterpillars (2 Duke of Burgundy’s, 2 large whites, 2 white letter hairstreaks)

Flora: Food sources: black currant, bilberry, cherry, red currant, wild strawberry

Objects: 4 Blackbird eggs, 7 blackbird feathers, 1 blackbird nest, The Langdale Rosary (altered to include an image of Saint Kevin)

Plants mentioned by Shakespeare: Black currant, bilberry, cherry, red currant, wild strawberry

Shakespeare’s Blackbird

Occurrences in text: 2

Plays: Henry IV Part 2, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Name as it appears in the text: “ouzel,” “ousel”

In Shakespeare’s aviary, we are never far from the topic of falconry, even when observing the blackbird, or “ouzel.” This springtime songbird was occasionally a prey bird for smaller hunters like the merlin and kestrel.[1] Surprisingly, Shakespeare focuses on the blackbird’s physical appearance despite the tempting opportunity for more falconry references.

The common blackbird has a glossy coat of onyx feathers that contrast its brilliant orange beak and ring encircling its eye. Shakespeare mentions the color orange only six times in his collected works, and one is attributed to the blackbird. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Bottom describes the blackbird in song to keep up his courage while wandering alone in an enchanted forest:

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Act III, Scene 1, Line 122)

BOTTOM: I see their knavery. This is to make an ass of

me, to fright me, if they could. But I will not stir

from this place, do what they can. I will walk up

and down here, and I will sing, that they shall hear

I am not afraid.[He sings.] The ouzel cock, so black of hue,

With orange-tawny bill,

The throstle with his note so true,

The wren with little quill—

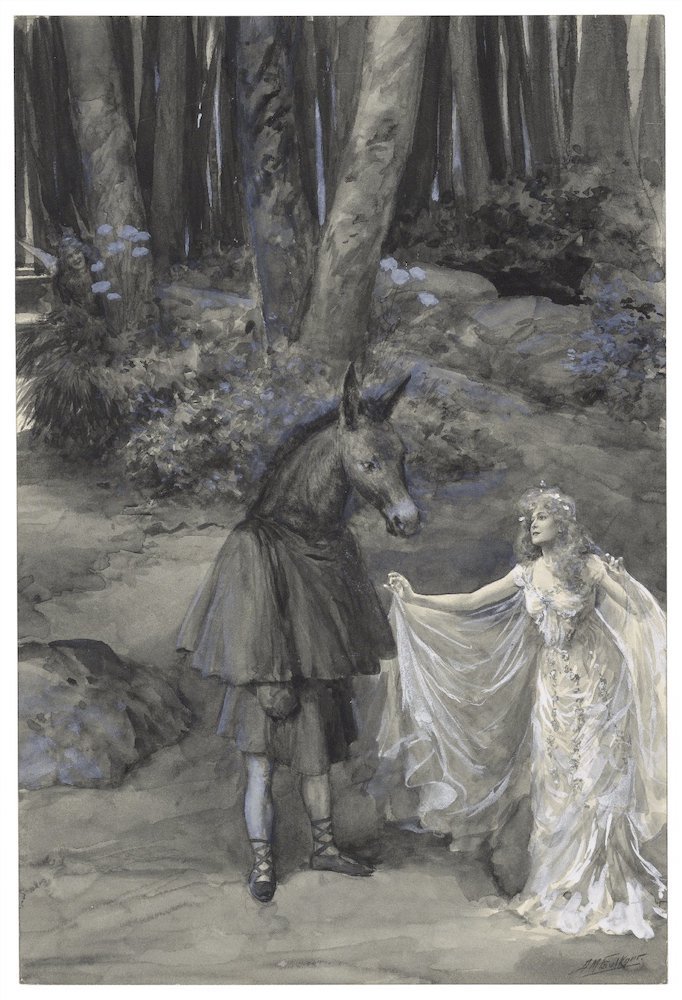

Bottom, transformed with an ass’s head, sings a tune about blackbirds to keep up his courage when he finds himself in strange circumstances. His song wakes the fairy queen, Titania, who falls in love with him upon first sight. Illustration by Charles Buchel (1905). Folger Shakespeare Library

The second appearance of the ouzel, found in Henry IV Part 2, is just as fleeting but not as straightforward. The line is debated among scholars:

Henry IV Part 2 (Act III, Scene 2, Line 5)

SHALLOW: And how doth my cousin your bedfellow?

And your fairest daughter and mine, my goddaughter

Ellen?SILENCE: Alas, a black ousel, cousin Shallow.

In The Birds of Shakespeare (1871), James Edmund Harting suggests that Silence’s “alas” indicates a contradiction. Silence is correcting Shallow that Ellen has dark hair, not blonde. The Norton Shakespeare has a different take. “Alas” could suggest disappointment at Ellen’s dark complexion.[2] Although the opinion is not palatable or shared by modern audiences, Elizabethan culture equated a light complexion with beauty. To call someone an ouzel was an insult because dark hues were seen as unattractive.[3]

I followed Bottom’s lead and created a painting that focuses on the ouzel’s striking black-and-neon palette. I surrounded the birds with their favorite colorful foods to complete the high-contrast image. These items conveniently emphasize the blackbird’s springtime associations. The blackbird sings a unique springtime tune that is clear, recognizable, and commonly heard in backyard gardens.[4]

When researching the ouzel, I found a charming tale about Saint Kevin (c.498), the first abbot of Glendalough, Ireland, canonized in 1903 by Pope Pius X.[5] The legend of Saint Kevin says he held out his hand in a courtyard to feed a blackbird, which built a nest in his palm.[6] Saint Kevin was so patient and kind that he stood with his arm outstretched until the chicks hatched and fledged.[7] His deep love and respect for nature is his defining characteristic as a saint figure.

An early illustration of Saint Kevin holding a blackbird within the margins Topographia Hiberniae, by Gerald of Wales, c. 1196-1223. In the collection of the British Library.

Link: Gerald of Wales, Topographia Hiberniae, 1196-1223. London, British Library, Royal MS 13 B VIII.

Shakespeare is a maximalist writer who loves detail—it seems that nothing escaped his observation. Therefore, when a detail is missing, I tend to read into it and attribute significance to the omission. Why did he pass over the blackbird’s religious tale? Shakespeare was writing in a profoundly Protestant culture; not referring to a Catholic figure may indicate the constraints under which he was creating. However, this theory is unlikely because of numerous examples of Catholic imagery in Shakespeare’s work. The answer may be more straightforward: perhaps he didn’t know about Saint Kevin and his ouzel, didn’t care for the story, or the opportunity never arose.

The blackbird introduces a recurring problem in my project: should my paintings exclusively represent how a bird is portrayed in the text or its broader Elizabethan reputations? I usually include these folktales, partially because they give me more to work with. Additionally, these stories were swirling in the atmosphere and were likely in the audience’s consciousness, even if they did not appear in the text or on the stage.

I wanted to incorporate a rosary to allude to the bird’s association with the Catholic saint. I sought rosaries from Shakespeare’s lifetime but came up short. Rosaries have been in use since the thirteenth-century but were banned in England during the Reformation.[9] Only one survived destruction—the Langdale Rosary.[10] This gilded rosary was owned by the Langdales of Houghton Hall, a Roman Catholic Family in Yorkshire, England. [11] It is now in the collection of the Victoria Albert Museum.[12]

My painting features the Langdale Rosary wrapped around the bird’s nest. Each gold bead features an etching of a different Catholic Saint or scene from Christ’s life.[13] The central pendant depicts the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus but I have replaced their image with Saint Kevin holding a blackbird.

The Langdale Rosary reminds us that Catholics worshiped secretly in England while their religion was outlawed for two hundred years, starting from 1559 under Queen Elizabeth I’s Act of Uniformity.[14] The rosary in my painting is present but obscured—much like Catholicism in Shakespeare’s lifetime.

Researching Shakespeare’s birds has led me down fascinating and unexpected paths. The blackbird dropped a breadcrumb at the feet of Saint Kevin, then at the Langdale Rosary, and then at the Reformation. Each bird presents a doorway to a new topic and an opportunity for a deeper understanding of Shakespeare’s writing, life, and cultural context.

Endnotes

[1] Harting, J., The Birds of Shakespeare, (London: John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row, 1871), 56.

[2] Shakespeare, William. "Henry IV Part 2." The Norton Anthology. 2nd ed. Eds. Greenblatt, Stephen, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard, and Katherine Eisaman Maus. New York: W.W Norton, 2008. Print.

[3] Shakespeare, William. "Henry IV Part 2." The Norton Anthology. 2nd ed. Eds. Greenblatt, Stephen, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard, and Katherine Eisaman Maus. New York: W.W Norton, 2008. Print.

[4] Harting, J., The Birds of Shakespeare, (London: John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row, 1871), 139.

[5] Haggerty, Bridget. “St. Kevin – founder of Glendalough.” http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Kevin.html. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[6] Haggerty, Bridget. “St. Kevin – founder of Glendalough.” http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Kevin.html. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[7] Haggerty, Bridget. “St. Kevin – founder of Glendalough.” http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Kevin.html. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[9] “The Langdale Rosary.” Victoria and Albert Museum Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2022. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O17851/the-langdale-rosary-rosary-unknown/. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[10] “The Langdale Rosary.” Victoria and Albert Museum Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2022. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O17851/the-langdale-rosary-rosary-unknown/. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[11] “The Langdale Rosary.” Victoria and Albert Museum Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2022. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O17851/the-langdale-rosary-rosary-unknown/. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[12] “The Langdale Rosary.” Victoria and Albert Museum Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2022. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O17851/the-langdale-rosary-rosary-unknown/. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[13] “The Langdale Rosary.” Victoria and Albert Museum Collections, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2022. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O17851/the-langdale-rosary-rosary-unknown/. Accessed on March 4, 2022.

[14] “19th- and 20th-Century Roman Catholic Churches,” Historic England, September 2017.